Female Nurse Suicide Rates Highest Of Any Profession

Disclaimer: This story discusses suicide and self-harm. If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide please call the 998 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 998, text TALK to 998, or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

Rhian Collins. Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara ER nurse. Michael Odell. Dr. Lorna Breen.

Three nurses. One physician. Four suicides.

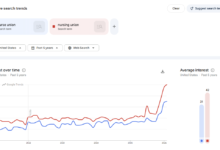

A study released in 2017 shed light on an alarming finding: of the female population, nurses are 23% more likely to commit suicide than women in general. Years later – this has changed and the percentage has only increased. The study linked this shocking statistic to nurses having easy access to lethal doses of medication and noted that suicide rates were higher amongst lower-paid healthcare employees versus higher-paid workers such as managers and CEOs.

Furthermore, nurses are four times more likely to commit suicide than people working outside of medicine.

While the risk of suicide has always been higher for nurses and other healthcare professionals – the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the numbers to rise at a drastic rate. So much so that the American Nurses Association (ANA) developed the Well-Being Initiative as a direct response to the pandemic. The Well-being Initiative gives nurses access to digital mental health and wellness-related sources, tools, and support. Developed ‘for nurses by nurses,’ the Foundation partnered with the American Nurses Association (ANA), the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), and the American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA).

“Nurses are putting their physical and mental health on the line to protect us all during this pandemic. Every day they confront traumatic situations while they face their own worries about the risks to themselves and their families,” said Kate Judge, executive director, of the American Nurses Foundation. “Nurses are always there for us and we owe it to them to support their well-being during this crisis and in the future.”

A study from researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and UC San Diego Health found that male and female nurses are at higher risk of suicide than the general population.

“Using the 2005-2016 National Violent Death Reporting System dataset from the Centers for Disease Control, we found that male and female nurses are at a higher risk for suicide, confirming our previous studies,” said senior author Judy Davidson, DNP, RN, a research scientist at UC San Diego. “Female nurses have been at greater risk since 2005 and males since 2011. Unexpectedly, the data does not reflect a rise in suicide, but rather that nurse suicide has been unaddressed for years.”

Researchers found that female nurse suicide rates from 2005 to 2016 were significantly higher (10 per 100,000) than the general female population (7 per 100,000). Male nurses (33 per 100,000) were higher than the general male population (27 per 100,000) for the same period.

“Opioids and benzodiazepines were the most commonly used method of suicide in females, indicating a need to further support nurses with pain management and mental health issues,” said co-author Sidney Zisook, MD, professor of psychiatry, UC San Diego School of Medicine. “The use of firearms was most common in male nurses, and rising in female nurses. Given these results, suicide prevention programs are needed.”

Suicide in the healthcare setting has been a long-standing topic of discussion. Suicide rates for doctors have been on a decline, especially after the aggressive support systems that have been put into place, and the reconstruction of work-life balance for many specialties.

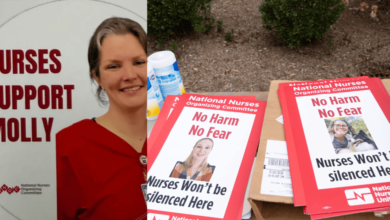

Image: Dr. Loren Breen

Despite the prior decline in suicide amongst doctors, not enough has changed. Dr. Lorna Breen, an Emergency Room (ER) physician at New York-Presbyterian Allen Hospital in New York City was on the front lines of the pandemic in March 2020 when the first wave of COVID-19 patients hit the country. Dr. Breen tragically took her own life while staying with her sister as a direct result of ongoing mental health struggles from her time working in the NY ER.

The Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act (HR 1667) was spearheaded by Senator Tim Kaine (D-VA) and was written to help spread the word regarding mental health within the healthcare community and to get adequate resources and funds to help those in need. The act easily passed the house of Congress and was signed into law by President Biden on March 18, 2022.

This law, while campaigned for by the family of a doctor, is intended to help all healthcare professionals. Through education, training, research, and overall awareness the goal is to dramatically decrease healthcare suicides.

But what about nurses? What is it about the profession, the lifestyle, and the work pressures that are contributing to this finding? What can we, as a nursing community, do to detect pressures, and increase the support systems for our fellow staff members or even, for ourselves?

The pressures of healthcare can be daunting; the high-speed inpatient setting, home health, and its shocking environments, and all the nursing positions in between put the nurse and fellow healthcare staff in humanity’s hardest moments. We are a profession that is made to ask “how are you?” But what if you don’t have someone to ask this of you?

Nurses are sandwiched between the demands of the patient and the demands of the system. When caring for patients, nurses are exposed to everything from debilitating diseases to traumatic situations. Without proper coping mechanisms – a support system to vent to after work, colleagues to share similar feelings with, a stable and supportive home life – the tragedies of daily work can take a toll on the nurse, one that is insidious and may not become evident until a breaking point is reached.

On the other side of the coin, nurses are often the cornerstone of patient care. Managing all healthcare specialties involved in that patient’s care (including other nurses themselves) can lead to a surmounting amount of pressure, and is a test of one’s confidence and self-worth.

The healthcare environment itself – traumatic patient situations aside – can be cut-throat and insensitive. Although every institution varies, it is common to enter a workplace environment that fosters an attitude of suppressed feelings and cold professionalism. In other words: if you have to cry over your patient during your shift, you’re not strong enough to be here. One Nurse wrote about her frustrating experience as a new nurse and feeling as if her job was an “abusive relationship.”

Nurses have historically been critical of each other’s practice and reaction to workplace stress, and although many hospitals have campaigned against nurse bullying, it takes more than a few posters to really change workplace culture.

More specifically, according to the National Academy of Medicine suicide risk factors for nurses are:

- Exposure to repeated trauma

- Scheduling long, consecutive shifts

- Repeated requests for overtime

- Workplace violence, incivility, and bullying

- Inadequate self-care

- Isolation from family and friends

- Fearing for one’s safety or the safety of loved ones

- Financial stressors

- Access to and knowledge of lethal substances

- Constant, high workplace stress

- Loneliness after relocation, transfer, or new job

- Issues with management

- Work/life role conflict

- Feeling unsupported in the role

- Feeling like you don’t belong

- Feeling unprepared for the role

- Fear of harming a patient

- Being evaluated for substance use disorder

- Depression

High Turn-Over And Workplace Violence

A study conducted by Vanderbilt University Medical Center found that out of new graduate nurses who leave their first job within the first six months, 60% did so because of some form of horizontal violence. But what about the ones who stay and tolerate the violence? Do they internalize it and take the hit to their self-worth? Do they, in turn, continue the practice of nurse bullying to future oncoming nurses thus potentiating the problem?

As we grow into more intuitive creatures, it is important to apply our advances to the healthcare setting: emotional intelligence towards preceptor-preceptee matching, support groups and outlets for healthcare workers to address feelings early, and a workplace environment that fosters speaking up about suicidal ideation, without stigma, and without judgment, for all the people who care for others at their worst.

While National Suicide Awareness Month is still several months away, the stigma and taboo of this topic must be addressed every month, every week and every day. It is also important to ensure that individuals, friends and families have access to the resources they need to discuss suicide prevention. NAMI is here to help.

- If you or someone you know is in an emergency, call 911 immediately.

- If you are in crisis or are experiencing difficult or suicidal thoughts, call the 998 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 998

- Safe Call Now – crisis referral service for public safety employees, emergency services personnel and their families. 206-459-3020.

- Disaster Distress Helpline – Call 1-800-985-5990 or text TalkWithUs to 66746. Run by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA). A 24/7, 365-day-a-year, national hotline providing crisis counseling for those in emotional distress related to natural or human-caused disasters.

- Crisis Text Line – 24/7 crisis support for frontline health workers from trained crisis responders. USA – Text “HOME” to 741741