Investigation: Massive increase in racial abuse against NHS staff

Each year, thousands of minority ethnic nurses in the NHS experience racism at work.

Some are subjected to physical or verbal abuse while on shift: being kicked, spat at or having objects hurled at them, due to race or ethnicity.

“‘Go back to your country’, ‘Black cow’, they spit in your eyes; I have been beaten black and blue because I am Black”

Elizabeth Nyakapanka

Others have been subjected to more covert and insidious racism.

They are denied promotions and development opportunities, they are the subject of gossip or are threatened with referral to the professional regulator.

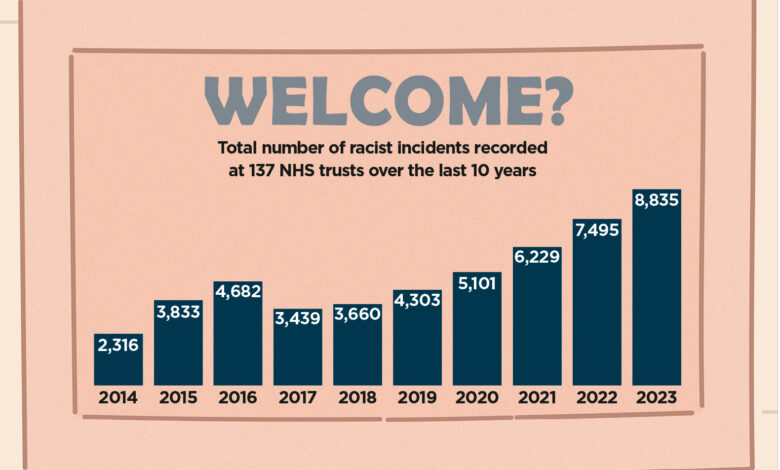

A new Nursing Times investigation has laid bare the scale of racism in the NHS over the last decade.

Our data supports anecdotal evidence by nurses that, despite awareness of racism increasing in recent years, the problem is getting worse, rather than better.

Under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act 2000, we asked every NHS trust in England to provide figures on incidents of racism between 2014 and 2024.

This data, which 137 trusts provided, was broken down into incidents of racism against staff by patients, and incidents against staff by staff.

In 2023, the latest full year for which data was provided, there were a total of 8,835 incidents of racism reported across the 137 trusts – equating to 24 incidents per day.

This figure is an 18% increase compared with 2022, and a 105% increase when compared with pre-pandemic levels back in 2019.

One trust provided Nursing Times with examples of incidents it had logged.

In one case, a patient was throwing chairs around the waiting area and using “racist and discriminatory” language towards staff; in another, two staff members were spat at and slapped after confronting a patient who was shouting racial abuse at their colleagues.

Around half (73) of all trusts that provided data reported more incidents of racism in 2023 than in any other year. At 30 trusts, the greatest number of incidents occurred in 2022, and for 20 most took place in 2021.

Meanwhile, 65% of all trusts reported an increase in racist incidents between 2022 and 2023.

In total, 28 trusts only provided Nursing Times with data for the last five years. However, of the 109 trusts that provided the full 10-year dataset, 85% reported higher incidents of racism in 2023 than in 2014.

In addition, figures from trusts that submitted data for one or all of the first few months of 2024 showed an incident count of 864 in that period alone.

Graph showing racial abuse reports over time

This comes as NHS England’s most recent Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) report found that Black and minority ethnic staff made up a quarter (26%) of the NHS workforce and more than a third (34%) of nurses, midwives and health visitors.

The same data also showed that Black and minority ethnic staff were overrepresented in lower-banded roles, with 42% on band 5 contracts compared with just 23% at band 6 and 18% at band 7.

Staff working at lower bands in the NHS are the least likely to report concerns about racial discrimination, because many believe nothing will change as a result, stated the report Too Hot to Handle: Why Concerns about Racism are Not Heard…Or Acted On.

The report, published in January by human rights and equality charity Brap, along with researchers at Middlesex University, also found that many staff were afraid to speak out about their experiences in case they faced repercussions.

One nurse told Nursing Times that speaking up about racism would only result in being “put through hell”.

Racism has been ‘normalised’ in the NHS

The increase in racist incidents towards staff is not always taken seriously in the NHS, claimed Elizabeth Nyakapanka, a senior mental health nurse manager and member of Uganda Nurses and Midwives Association in UK.

She told Nursing Times that racism had become so “normalised” that many Black nurses did not report it. “It’s day-to-day in mental health,” she said.

In her role, Ms Nyakapanka – who trained in Uganda but has practised nursing in the UK for more than two decades – has been verbally abused frequently by mental health patients: “‘Go back to your country’, ‘Black cow’, they spit in your eyes; I have been beaten black and blue because I am Black.”

“Patients attack nurses, [they think] ‘I am in my country, my territory’. They look at you, a foreigner, restricting and depriving them,” she added.

Ms Nyakapanka described a “tug of war” between trying to get trusts to take incidents of racism seriously, and trying to encourage staff to report them when they happen.

She said: “[Nurses] tell me, ‘Why should we waste our time? Even if we complete the incident form, nothing is going to happen.’ Every day the less-serious [incidents] will not be reported.”

At the 2023 NHS Confederation Expo, leading NHS figures acknowledged the “corrosive” – as Nursing and Midwifery Council chief executive Andrea Sutcliffe described it – effect racism had on the health and wellbeing of the workforce and the fact Black and minority ethnic nurses were leaving the profession because of it.

Ms Nyakapanka described a vicious cycle she had observed over the years: workforce shortages lead to more incidents, the victims of which end up taking time off to recover, causing more gaps in rotas to form.

“If every day we have [dozens of] staff on recovery leave for one-three days, how much is being spent on bank and agency to cover for them? Some have life-changing injuries [from racial abuse incidents], and it has affected patient care,” she said.

Neomi Bennett

“Nurses are frightened; they are very frightened.”

Neomi Bennett, founder of Equality 4 Black Nurses, a peer-led support network for Black nurses who have faced discrimination at work, told Nursing Times that the FOI data was “no surprise” and the rise in racism against staff was “not new”.

Even when nurses have escalated and reported incidents of racism, many have been “gaslit” by colleagues, who insist it is not as severe as they are saying, said Ms Bennett.

In some cases, Black nurses who have escalated their experiences of racial discrimination have uncovered that any references to racism have been “deliberately omitted” from incident reports, she added.

What is driving the increase in racist incidents?

Many nurses have linked the rising incidents of racism over the last decade to the increasingly polarised political climate in the UK.

Dr Ruth Oshikanlu, an independent nursing leader, said the current “environment we live in” had enabled discriminatory behaviour. She added: “People are getting more brazen and comfortable in their skin to really show it. Whereas racism was more covert before, now it’s more overt.”

Political decisions had also played a role in whipping up tensions around immigration and foreign workers, according to Dr Oshikanlu.

She argued that the government’s recent visa-tightening rules were one example of this, whereby overseas care workers have been banned from bringing dependents with them on their visa. She said: “We have a government policy that says you can come here to work, but you can’t bring your children or your family – how is that, in itself, not racist?”

Similarly, some nurses told Nursing Times that the Brexit result in 2016, when the UK voted to leave the European Union, bolstered nationalism and subsequently racism: that year saw the number of recorded incidents rise to 4,682 from 3,822 in 2015 – a jump of 22%.

Other recent global events have also caused tension on wards, staff have reported.

One South Asian midwife, who did not wish to be named, told Nursing Times that the Black Lives Matter movement, following the death of George Floyd in 2020, caused her to be “interrogated” by White colleagues.

“It made a lot of people, especially White colleagues, really, really defensive,” she explained. The same midwife has noticed similar trends following the outbreak of the ongoing conflict in Gaza.

She gave one example of a Muslim midwife being probed by colleagues about Palestinian militant group Hamas. She said: “It’s like, are they conflating a woman with a headscarf to a terrorist organisation? How do I, as a marginalised midwife, support another marginalised midwife to escalate that?”

Rohit Sagoo, founder of British Sikh Nurses, suggested a recent influx of internationally-trained nurses as well as a general cultural shift in the country could be further driving incidents.

“[Some internationally trained nurses] are moving to places of very low minority ethnic populations, like the South West of England. Let’s say you’ve got 2,000 Indian nurses that just come into Truro, in Cornwall, you’ve got a population which is predominantly White, you’re going to be ruffled,” he said.

Just the tip of the iceberg

Nursing Times believes the figures we have obtained only scratch the surface of how much racism is taking place against NHS staff, particularly among colleagues.

Over the 10-year period across all trusts that differentiated between incidents committed by patients and those committed by staff, there were only 784 recorded incidents of racism by staff against staff, compared with 42,518 incidents committed by patients against staff.

Some 126 trusts reported zero incidents of staff-on-staff racism over the last decade, with 112 of those doing so because they did not hold any data on it.

However, nurses have told Nursing Times that racism among colleagues is an “everyday occurrence” and the likelihood is that it is not being reported due to fears about speaking out.

In addition, staff-on-staff racism can often be hard to report due to the insidious and covert ways it manifests.

As an example, Equality 4 Black Nurses has seen an exponential rise in disciplinary action against Black nurses.

“The NHS is regarded as a treasure, it’s almost blasphemy if you go against what the system”

Rohit Sagoo

Ms Bennett said: “The disproportionate disciplinary actions towards Black staff are at boiling point. Often the allegations are unfounded, there’s no evidence [and] it’s a pathway from disciplinary action to the NMC.”

The rise in referrals to disciplinary processes has come because of “negative perceptions of Black nurses’ competencies and professionalism”, argued Ms Bennett.

“It leads to close scrutiny and harsher performance evaluations; being stereotyped as less capable or more prone to make mistakes actually influences disciplinary actions against them,”she said.

Ms Bennett warned that NHS organisations “don’t actively address racism and discrimination”, and recent endeavours by trusts to do so were mostly “lip service”.

She added: “NHS organisations actually perpetuate an environment in which Black nurses are treated differently and are disproportionately disciplined.”

Similarly, children’s nurse and British Sikh Nurses founder Mr Sagoo described the FOI data as “startling”, but said it matched his personal experiences. He agreed that the figures were the tip of the iceberg.

Mr Sagoo said that internationally educated nurses, who may face further discrimination compared to British-born minority ethnic people due to their accent, were both at greater risk of a racial abuse incident and less likely to report one.

“I think they probably have a fear that they can’t report for fear of losing their job, their visa status, etc,” he said.

What is missing from the figures is as important to consider as what can be seen in them, according to Mr Sagoo, who said the low reported numbers in some areas of the data – such as staff on staff incidents – was a sign that a lot of incidents go unreported.

Rohit Sagoo

He criticised a lack of a “robust system” for reporting racist abuse in much of the NHS and expressed a fear among minority ethnic nurses that, when a report is submitted, either nothing will happen or they will face detriment.

“The fear is that when a report goes somewhere, it goes to HR, and most HR sides with the organisation,” Mr Sagoo said.

“And if you’re taking on the NHS, it’s a massive thing and you get shot down before the process even begins… the NHS is regarded as a treasure, it’s almost blasphemy if you go against what the system and the rules are.”

The NHS’ freedom to speak up scheme, Mr Sagoo added, should be facilitating such reports and actions on racist abuse towards nurses.

However, he said that in his experience many speak up guardians were limited in their ability to address racism due to a lack of lived experience.

“We need a separate kind of system, separate to speak up guardians. A racial reporting officer who you go to who is of an ethnic minority [and] understands it.”

Bullying, isolation and intimidation

Dr Ruth Oshikanlu, a nurse who has been leading work around anti-bullying in the NHS, said racism also manifests itself through bullying.

Ruth Oshikanlu

This could include White managers giving minority ethnic staff the worst shifts or the most challenging patients, denying them something to which they are entitled or refusing them promotions and development opportunities.

For internationally educated nurses, this could also manifest as “threats” to revoke visas or work permits for not conforming.

One intensive care nurse, who did not wish to be named, told Nursing Times she had experienced months of relentless bullying by her manager, which she believed was motivated by racism.

The nurse, from India, described a turbulent 12 years trying to climb from a band 6 to a band 7.

“They do say that you [should] speak up but, when you speak up, your life will be put through hell”

Anonymous nurse

During this time, her manager was overheard saying she would “make sure she doesn’t get band 7” and would “use all her power” to ensure the nurse would no longer work at the trust.

This targeted behaviour then escalated when the manager rounded up a group of colleagues and asked them to all put in a formal complaint about the intensive care nurse.

These people, whom the nurse had considered friends and allies, had been asked to speak ill of her despite not believing that she had done anything wrong. The nurse subsequently took three months off due to stress.

She explained that racially motivated bullying incidents like this were “hard to prove” but were happening to minority ethnic staff across the UK.

“How can I challenge this as a junior, as an ethnic minority?” she asked, adding: “They do say that you [should] speak up but, when you speak up, your life will be put through hell.”

The experience of international nurses

The NMC’s inaugural Spotlight on Nursing and Midwifery report, published last year, revealed that internationally educated nurses had been left feeling traumatised because of the racist and derogatory comments they faced at work.

Internationally educated nurses reported often feeling unsupported by, and unable to trust, their colleagues.

Sam, an international nurse who only wanted to provide his first name, told Nursing Times our FOI data was “only a fraction” of what was actually happening and recounted how he experienced so much targeting at work, he had to leave his trust altogether.

Sam tried to escalate a situation at his trust, where he felt he was “not fairly treated” by colleagues due to the colour of his skin. Instead of listening to his concerns in confidence, however, his managers launched a formal investigation without him knowing, which resulted in them bringing into question his capability in his role.

“We’ve had staff who have ended up in our emergency department having been hit, we’ve had people having their teeth knocked out”

Kathryn Halford

What was supposed to be a confidential discussion about discrimination in the workplace led to Sam being “framed and targeted” by NHS managers, he said. He later stepped down due to stress.

“Speaking up requires a certain degree of courage, but sometimes everything becomes silent after that,” Sam said. “You should not be worried about [speaking up], but you see the silent repercussions.”

Marimouttou Coumarassamy

Marimouttou Coumarassamy, founder of the British Indian Nurses Association (BINA), told Nursing Times that the shock of racism “affects the confidence” of many nurses who have come here from overseas.

“It’s very new, we are not going to be experiencing that in our own country,” he said.

“Coming here and just based on the colour of our skin, people are giving that much abuse? That’s new. So it affects our confidence because are trying to settle in [and] we are trying to integrate in the communities, we are trying to learn.”

Mr Coumarassamy said he believed reporting of racism had gone up in recent years, which he linked to the growing diversity in leadership positions across the NHS.

However, he argued that all trust leaders needed to be “accountable for their actions” especially when it comes to eradicating racism.

He likened tackling racism to tackling other key performance indicators in trusts, like reducing ambulance wait times, and argued that data should be gathered in a similar way so progress can be measured.

“I think they need to be very clear [about] what they are agreeing to deliver and how they are going to be transparent about that,” added Mr Coumarassamy.

How NHS trusts have responded

Some NHS trusts have seen the rise in racism against their staff and taken action.

After recently observing an almost doubling of violence and aggression – including racism – towards its staff, Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust started a campaign to tackle it.

No Abuse, No Excuse has seen the trust introduce 60 new body-worn cameras for clinical staff and improvements to its yellow and red card system, which allows staff to give patients and their families formal warnings if they are abusive.

Chief nurse Kathryn Halford told Nursing Times the national trend of rising racist abuse matched with day-to-day observations at her trust.

Kathryn Halford

“Some of [the abuse] is extremely racist,” she said.

“We’ve had people told to ‘go back to the jungle’, we’ve had staff who have ended up in our emergency department having been hit, we’ve had people having their teeth knocked out. This is not insignificant stuff.”

Meanwhile, Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust has created a system that allows staff to report instances of microaggressions – subtle, indirect or potentially unintentional discriminatory behaviours.

Responding to Nursing Times’ findings, an NHS England spokesperson said: “Everyone working in the NHS must feel safe from any form of discrimination or abuse, feel able to raise concerns, and be confident that these concerns are taken seriously and acted on.

“NHS England, working closely with the National Guardian’s Office, has published guidance and policy to support organisations to strengthen their speaking-up arrangements and culture, and we continue to work closely with NHS organisations to embed actions to address prejudice and discrimination as part of our equality, diversity and inclusion improvement plan.”