Keto Diet: Healthy or Harmful?

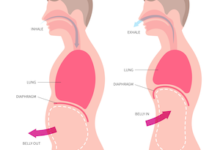

With a multitude of popular diet trends circulating in society today, it might be difficult to discern the different aspects of each. As a healthcare provider, it is important to understand these fads as nutrition plays a significant role in the health of your patient. One common diet is the ketogenic, or “keto” diet which consists of a high fat, low-carbohydrate, and moderate protein (1 gram/kg) regimen. How does it work? Our cells typically utilize glucose from carbohydrates for energy. Without glucose, the process of ketosis kicks in where the cells break down fat into ketone bodies to create energy. This shift to fat metabolism results in weight loss.

The keto diet is not new, rather it has been an effective nutritional therapy used to treat epilepsy since the 1920s. This treatment was based on the theory that the liver produces ketone bodies (acetoacetate, acetone, and beta-hydroxybutyrate) from long- and medium-chain fatty acids which act as anticonvulsants when they cross the blood-brain barrier (Kossoff, 2019).

Four Types of Ketogenic Dietary Therapies (KDTs) (Kohli & Samour, 2013)

- Classic Ketogenic Diet

- Fat is derived from long-chain triglycerides in the diet and provides 90 percent of the calories.

- Protein is based on the amount needed for adequate growth.

- Carbohydrates are restricted.

- Ratio of fat to nonlipid is 4:1 (four parts fat to one part protein and carbohydrate).

- Optional twenty-four-hour fasting period prior to initiation.

- Studies have shown a reduction of seizures by more than 50% (Kossoff, 2019).

- Medium-Chain Triglyceride Diet

- Oil supplements (i.e. coconut) serve as a major fat source and provide 60% of the calories.

- Yields more ketones that are more easily absorbed and carried directly to the liver.

- Less total fat is needed and more protein and carbohydrates can be used.

- Similar epilepsy reduction efficacy compared to the classic ketogenic diet.

- Modified Atkins Diet

- Alternative to KDT and allows for more protein.

- Carbohydrates are limited to 10 grams per day.

- Lipid to nonlipid ratio is 1:1 or 2:1.

- Ketosis occurs during the first month of initiation and may correlate with seizure control.

- Diet is more tolerable and results are similar to classic ketogenic diet when maintained for more than six months (Kossoff, 2019).

- Low Glycemic Index Treatment

- Limits carbohydrates to 40- 60 grams per day and to only those with a low glycemic index (<50).

- No restrictions on fluids or protein and loosely monitors fat and calories.

- Lower efficacy compared to other keto diets.

Epilepsy Treatment (Kossoff, 2019)

Several epilepsy syndromes that have shown improvement with KDT treatment include: Doose syndrome, Dravet syndrome, GLUT-1 deficiency, infantile spasms, pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency tuberous sclerosis complex, and super-refractory status epilepticus.

- Patients with epilepsy being treated with a KDT should be monitored by a trained dietician and neurologist.

- These diets may be started in a hospital setting or in an outpatient clinic.

- Pediatric patients are typically administered multivitamins with minerals (selenium), calcium, and vitamin D supplements.

- Clinical response may be seen within a few weeks and a decrease in seizure frequency within two to three months.

- Follow-up visits should be scheduled at one month, then at three, six, nine and 12 months during the first year of treatment.

- Monitor labs every three months during the first year including: complete blood count with platelets, metabolic profile, fasting lipid profile, calcium, vitamin D, and magnesium. Treatment is typically recommended for a maximum of two years.

- Monitor your patients for adverse effects such as gastrointestinal symptoms, dyslipidemia, hypoglycemia, constipation, growth failure, bone disease, kidney stones, and selenium deficiency.

KDT is contraindicated in patients with (Kossoff, 2019):

- Metabolic disorders that disrupt the oxidation of long-chain fatty acids and result in catabolic crisis. These include deficiencies in primary carnitine, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I or II, carnitine translocase, medium-chain acyl dehydrogenase, long-chain acyl dehydrogenase, short-chain acyl dehydrogenase, long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, or medium-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA.

- Fatty acid beta-oxidation defects.

- Porphyria: KDT may worsen acute intermittent porphyria or metabolic disorders caused by changes in enzyme activity related to heme production. Porphyria is an absolute contraindication for KDT.

Keto diets may also exacerbate chronic medical issues such as kidney stones, hypercholesterolemia, liver disease, gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, cardiomyopathy, and chronic metabolic acidosis (Kossoff, 2019).

General Weight Loss

Short-term use of low-carbohydrate diets can be an effective weight loss method. These diets may also benefit patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance that manifests as obesity, dyslipidemia (high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol), hypertension, high blood glucose, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction (Volek & Phinney, 2013). However, reverting back to the prior carbohydrate intake may negate any benefits gained.

Conclusion

The effects of a keto diet will vary among individuals and may not be right for every patient. If your patient does not have an epilepsy disorder, type 2 diabetes, or metabolic syndrome and they are exploring the keto diet, be sure to provide support and information to guide them in this decision.

References

Kohli, A. & Samour, P.Q. (2013). Use of the Ketogenic Diet in Adults. Topics in Clinical Nutrition. 28(2), 105-119. DOI: 10.1097/TIN.0b013e31828d7866

Kossoff, E. (2019). Ketogenic dietary therapies for the treatment of epilepsy. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ketogenic-dietary-therapies-for-the-treatment-of-epilepsy

Volek, J.S. & Phinney, S.D. (2013). A new look at carbohydrate-restricted diets: Separating fact from fiction. Nutrition Today. 48(2), E1-E7.