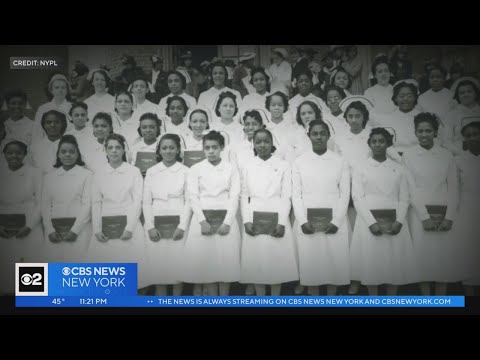

The Untold Stories of 7 Black Angels, Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis

Guest Post By Maria Smilios, Author of The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis

In early 1929, White nurses at Sea View Hospital in Staten Island began hanging up their uniforms and walking out. Their reasons for leaving varied: some cited the grueling five-hour round-trip commute from Manhattan to Staten Island; others said it was the mental and physical toll the job demanded.

Most White nurses were leaving to escape tuberculosis, the “great white plague,” that was killing their colleagues at Sea View, a sprawling municipal sanatorium known as the “pest house,” filled with New York’s poorest, people the city considered expendable “uncouth, immoral, indigent” consumptives. That’s who was sent to Sea View.

Woefully understaffed and underfunded, the hospital was perched high on an isolated hilltop miles away from the ferry port and the vibrancy of city life. Inside its wards, thousands of patients, mostly immigrants, Black people, and those on the fringes of society, lay languishing, waiting to die. Stigmatized and ostracized from their communities, many stayed for months or years, their only contact being the White nurses who cared for them. But now, they were leaving and miring the city in a crisis: if health officials couldn’t staff the ailing Sea View, they would be forced to close wards, and hordes of sick and infected patients would converge on the streets, spreading disease, raising the death toll, and creating a public health catastrophe.

Recruiting Black Nurses To Staten Island

Emergency meetings ensued about who would replace the Sea View nurses. Then an idea emerged: Black nurses.

In almost two decades, the Great Migration had brought thousands of southern workers north to work in factories and steel mills and as cooks or domestics. Nursing wasn’t the same kind of labor, but the lines of segregation had left enough Black nurses unemployed–in 1929 there were only 260 Black hospitals versus 6000 white ones.

To ensure they came, the city would offer a package: a job in one of its four integrated hospitals—at the time only 4 of the 29 municipal hospitals hired Black nurses–steady pay, housing, free education, if needed, at Harlem Hospital, and most of all an escape from the strictures of the south.

The call went out and moved down the eastern seaboard, crossing the Mason-Dixon line into Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia. Soon the Black nurses began arriving.

For decades, they worked at Sea View, enduring racism, sexism, verbal redlining, and physical abuse from patients; they were also ostracized by Staten Island residents who sneered and shunned them on public transportation, and most of all, they worked day after day onwards with a deadly disease that had no cure.

Isoniazid Drug Trials and Ending TB

Then in 1952, they became part of the isoniazid drug trials, and in a galvanizing moment in time, helped change the course of global history—Dr. Robitzek said, “Had it not been for the Black nurses none of this [the trials] would have been possible.” And until the publication of The Black Angels book, these women had been completely erased from history.

From 1929-1961, when Sea View finally closed, hundreds heeded the call to work. These nurses are known as The Black Angels, and while every single one of them deserves their story to be told, here’s a glimpse into seven of their stories.

1. Edna Sutton

In 1929, Edna arrived at Sea View from Savannah, GA, where she was born into abject poverty. The oldest of six she was a natural caretaker and a brilliant student who loved literature, Latin, drama, and science, especially biology. Her first dream was to become a surgeon, but many said it was unrealistic, as Black women “rarely left Savannah,” let alone become surgeons. Her father, an enslaved man who walked off his plantation and reinvented himself as a preacher, inspired his oldest daughter to dream big, something she took to heart.

While her dreams of becoming a surgeon never materialized, she eventually found her way into an operating room: Sea View hired her as one of the few surgical nurses, a highly sought after and demanding job—in the early 1930s, surgery, after the “rest cure,” surgery was the gold standard for treating tuberculosis, and the nurses tasked to work on the surgical ward were regarded as “the best.”

Edna spent over two decades working at Sea View, enduring the wrath of a White supervisor who refused to allow the nurses to wear masks (they would be complacent, she believed); she worked during the dark pre-antibiotic days, assisting in brutal operations where ribs were “removed in bushels, six to eight at a time,” and chest cavities were stuffed with wax packs or ping pong balls to keep the lungs collapsed.

In addition to her work at Sea View, she, like many of the nurses, was involved in her church—Bethel Community Church, and organizations such as the NAACP and NACGN that were working toward Black nurses gaining equality in the profession. Edna pushed against the red-lining rampant in Staten Island by becoming one of the first Black nurses to buy a house on Bradley Avenue, an area the city had designated as “definitely declining” because of the “influx of [the] negro population.” Despite the categorization, Edna’s home became a cornerstone for what soon materialized into a new middle-class Black neighborhood, one heavily populated by professional nurses.

2. Missouria Louvinia Meadows-Walker

Missouria came to Sea View by way of Howard University, where she studied under Estelle Massey Osborne and Mary McLeod Bethune. After graduating, she worked closely with Dr. Charles R. Drew. Originally from Clinton, South Carolina, she was the eighth of twelve children raised by her mother, “Mama Amy,” who taught her daughter to read the stars, love stories, be fearless, value education, history, and herself.

Growing up, she worked in the cotton fields before school and on the weekends. She was a stellar student who loved history, literature, Jazz, and medicine. Her nephew said Missouria dreamed of becoming an nurse, “changing the world,” and seeing “equality for all Black people.”

At Sea View, Missouria worked on the men’s ward, often a dangerous place, as the men tended toward violence—one nurse likened it to “a bawdy bar at night.” In her time there, she tolerated a daily barrage of racially charged verbal abuse and, for a year, she was relegated to care for a Nazi POW, a gravely ill, rage-filled man who wanted to kill her by infecting her with TB.

Despite all this, Missouria prevailed.

“This was her calling,” her niece said, “and she stayed the course and believed God would help work it out.” In the mid-1940s, she was finally promoted to supervisor for the ward and, in 1952, was chosen to oversee the isoniazid trials.

While at Sea View, she was a fierce and devoted advocate for nurse’s rights, and she established a fund for nurses in her church—St. Philips Baptist Church. Unable to have children, she opened her home to anyone who needed a place to stay, and raised many of her nieces and nephews, teaching them about their history (Missouria believed that only by knowing the past could anyone move forward.) When she retired, she continued her professional duty by caring for people in her neighborhood; in some cases, she bought beds to care for the sickest in her home.

3. Clemmie Phillips

Clemmie was born in 1904 in Bainbridge, GA, a rural and bucolic town that sat in the middle of three rivers, Flint, Chattahoochee, and Apalachicola, and was rife with Native American lore. Growing up, Clemmie’s family was beset by poverty. She lived in a 3-room shotgun house with no electricity and a single mother who was a laundress. Beset by anxiety and grief—her husband, a preacher, died from TB when Clemmie was two—she struggled to raise her children and reconcile that four older sons abandoned the family to find work, but, as her granddaughter said, fell in “with bad people.” The burden to help fell on Clemmie, and from the age of 5, she began washing and folding clothes—throughout her school years, on Fridays, her mother would keep her home to work.

Despite the weekly disruption, Clemmie excelled at school and, eventually moved to Savannah to attend the Georgia Infirmary, a down-and-out charity hospital that worked on a barter system: students received free training in exchange for working on the wards. In her second year, she had a daughter, but the father left, leaving her to raise the baby alone. Like her mother she struggled financially—then Sea View presented itself. Knowing this was the only way forward, Clemmie, was forced to leave her baby in Savannah with, as her granddaughter described “a very cruel and militant” sister.

At Sea View, she worked hard, and her outstanding work ethic impressed the nearly unimpressible White supervisor, who promoted her to a Charge nurse within two years, enabling Clemmie to bring her daughter north.

4. Phyllis Alfreda Hall Lambert

Phyllis was born in 1909 in the rural town of Alachua, FL–in 1905 it had a population of 526 residents. It was a hub for the cotton industry that helped to expand the town. Phyllis came from a large family that struggled with poverty. Her grandfather was a Methodist minister, and at some point, according to her family, she was sent to the Baldwin School for Colored Girls.

After she graduated, she enrolled in the George E. Brewster School of Nurse Training in Jacksonville, FL. In 1940, she was recruited to Sea View where she worked for almost 40 years. She owned a home on Bradley Avenue, and her family described her as “outgoing and friendly, a mostly happy and caring person, who loved her job.”

5. Marjorie Tucker Reed

Marjorie was born in Norfolk, VA in 1925, and came to Staten Island when she was 10. In 1946, she became a single mother. Broke with an infant, she answered an ad for aides at Sea View for which she applied and was immediately hired. The job awakened her love for nursing, and through a work-study program, she received her degree and began a career as a pediatric surgical nurse at Sea View where, she said, “they were taking out lungs by the dozens.”

Of the many things Clemmie told me in our interviews, she vividly recalled riding the 111 bus from the Staten Island Ferry terminal to the hospital. “The people, they moved away from me,” she said, “like I had the plague. Like the germs were going to jump out at them.”

She also talked about the Black nurses being sent to Sea View, “At Sea View Black nurses knew they could get hired, but at the other hospitals they knew they would be put through the wringer, and the end line was that they weren’t going to be hired…[so] they came here in droves…it was a good opportunity for nurses down in the south to come here and have room and board. That’s the way it was in TB time.”.

6. Kate Gillespie

Born in 1899 in Selma, AL, Kate was raised in the small town of Bessmer, ninety-one miles from Montgomery. She was the oldest of ten children born in succession to her mother, who was strict about education and the ethic of hard work, a trait that Kate embraced. Her father Thomas Anderson, an imposing and serious white man, with striking blue eyes he passed on to Kate, was 40 years older than her mother. His success as a farm worker and cattle owner allowed Kate and all her siblings to focus on one thing, school.

After graduating from Hale Nursing School, she worked in Alabama for years, but in 1932 she took a job at Sea View to “escape the south and its violence,” her granddaughter said, and secure a better life for her five-year-old son. Once, her family asked her why she left, and she answered, “There was strange fruit growing on trees.”

While at Sea View, Kate was in charge of the Employee Clinic, but in the mid-1940s, she was promoted to a supervisory role and moved to the adult wards. According to her family, she was a lifelong activist for labor rights, and advocated alongside A. Phillip Randolph.

Kate was one of the few nurses who didn’t move to Staten Island, “she loved Harlem and its culture, but mostly, Staten Island, reminded her too much of the south she wanted to leave behind.”

7. Virginia Allen

There is so much to say about Ms. Allen, as she’s been with me from the outset of this journey and her story opens my book. Recently, a spate of articles from the New York Times to the the Campaign for Action have highlighted her life and contributions to nursing in great depth. But, here’s a small taste of Ms. Allen, who at 92, is one the last living Black Angels.

Born in 1931, she always wanted to be a nurse because, she said, “I would see my aunt Edna in her nurse’s whites,” and “I was inspired.” In 1947, at a mere sixteen years old during a dire nursing shortage, Edna invited her to come to Sea View where she was hired as a nurse’s aide in the Children’s Hospital. Some said it was the “saddest place on earth,” but Virginia remembers her time there fondly, “maybe because I was so young,” she said, “I found it a challenge, not a chore, but I also knew the children were very very sick.”

Fortunately, she began working during the golden age of antibiotics where more treatments were available for those sick with TB. In 1952, she, along with her colleagues, became part of a galvanizing moment in history, the isoniazid trials which ushered in a cure for tuberculosis; although the children were not part of the trial, Ms. Allen was privy to this long-awaited moment, “it was very exciting to see more patients going home.”

Following Sea View, she graduated from the School for Practical Nursing as an LPN and embarked on a long career in nursing. In addition, she began deeply involved in civil rights and her community. Now retired from nursing, she remains an essential part of her Staten Island community, serving on various boards, championing women’s issues, and continuing to advocate for education reform and youth development. She loves music, art, literature, theater, and traveling. She has always been guided by this principle, “This world is all we have, and it is our duty to care for one another with love.”

The Black Angels Book

Order The Black Angels book on Amazon

Maria Smilios was born and raised in New York City. In 2016, while working as a developmental editor for Springer Science she learned about this extraordinary story and became determined to tell it. She holds a Master of Arts in American literature and religion from Boston University where she was a Luce scholar and taught in the religion and writing program. This spring she will be teaching a writing class at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Narratively, The Forward, Lit Hub, Writers Digest, Dame Magazine, The Rumpus, and other publications.

The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis is her first book.

You can find her at mariasmilios.com